It’s hard to know where to start an open-ended newsletter discussing a whole era. I’ve tried to set the tone by kicking off with Robert Musil and his disdain for the whole culture (vibe?) of late Imperial Vienna.

Where to next? The music? Certainly Richard Strauss, Gustav Mahler, and Arnold Schoenberg will have plenty of space to come. The politics? No, Musil already has touched upon that, and it can get tedious fast. I will work politics into almost every single post without making it too much of a focus, at least early on. Philosophy and psychology will also play their part with Wittgenstein and Freud playing important roles. Art with Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele and the entire Vienna Succession phenomenon will be addressed.

But after much consideration, it seems that it’s impossible to talk about late 19th / early 20th century Vienna and the entire Austrian-Hungarian Empire without addressing, directly, the Ring Road. In German, die Ringstraße.1 The construction of the Ring Road was the fundamental architectural project of the period in Vienna and the Empire, lasting by some measures throughout the entire period. It transformed Vienna from medieval to modern in a very short period of time and provides the cultural nexus around which most of the activities mentioned above take place. Today, when you think of Vienna, you think of the Ringstraße.

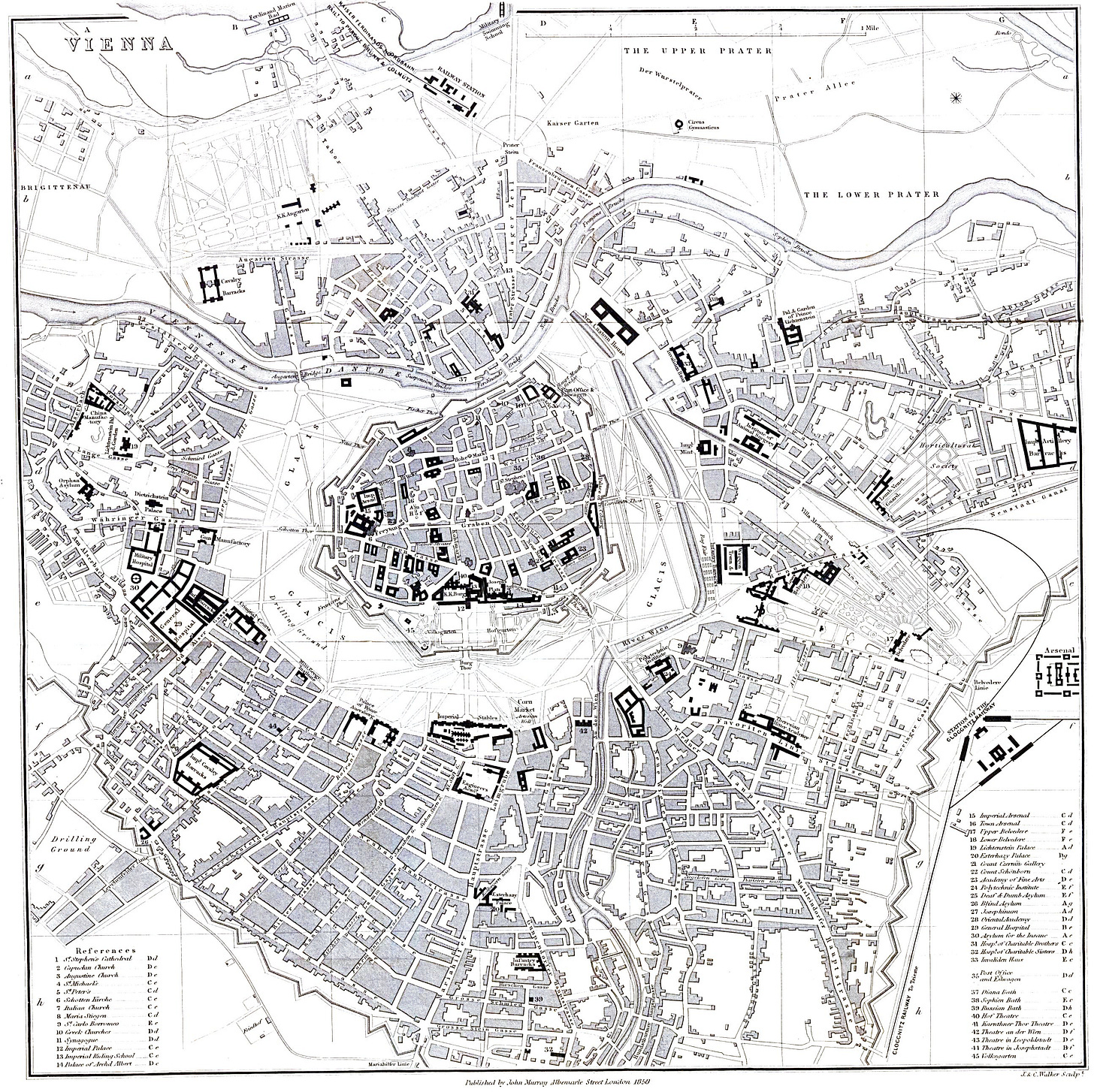

Medieval Vienna

As late as the 1850s, Vienna was a medieval city. The map above (public domain, from wikipedia) is from 1858 and shows the inner city, still walled, then the large open field outside the wall called the glacis, criss-crossed with paths and road. Outside of that begins the so-called suburbs, although these are part of the city of Vienna. For those looking for a bit of trivia: the walls of Vienna were built from the ransom money demanded by Austria when they captured Richard the Lionheart on his return from the crusades in the 13th century.

Liberal ascendency; down come the walls2

The European-wide Year of Revolution (1848) was a short-term failure for liberal revolutionaries in Vienna. However, it showed the Austrian military to be largely incompetent, and their grip on the Emperor and government was gradually loosened. And era of liberal reform began and with that ends the military’s ability to block development of the glacis outside of Vienna’s medieval walls. In December 1857, Emperor Franz Joseph I declared his intention to open up the space to civilian uses. The walls would come down and the space would be dominated by a wide road encircling the inner city, all very reminiscent of Baron Haussmann’s renovation of Paris, already begin 3 years before.

Land around the main road on the former glacis was given to the City Expansion Fund, created in 1858, which operated as a private company, selling the land and requiring construction for projects be completed in relatively short periods of time. The machinations of the City Expansion Fund may warrant a post on its own in the future, as I see from the news that it dissolved only in 2017!

Regardless of how they were funded, the buildings of the Ringstrasse displayed a jumble of styles: Gothic, Renaissance, Classical and in the later days, thoroughly Modern. The words sometimes used are “eclectic historicist.” That’s awfully academic and certainly a bit of an insult. The more polite term is Ringstraßestil (Ring Road style).

Let’s look at few of the notable buildings on the Road.

Votivkirche

Begun in 1856 and finished in 1879, the Votivkirche was one the first monumental buildings constructed on the Ring Road. It is dedicated to the memory of Emperor Franz Joseph I surviving an assassination attempt in 1853 and was funded by donations from around the Empire. It’s aggressively neo-Gothic design set the historical tone for much of the subsequent buildings.

The Austrian Parliament Building

It certainly doesn’t get more neo-Classical than that. Complete in 1883, it features a statue of Pallas Athena (pictured here) which was added in 1902. Carl Schorske in his essay on the Ringstraße (see footnote 2) makes much of the fin-de-siècle Austrians struggling to connect their history to the neo-Classical design of this building. There’s very little Austrian, or Germanic in this at all, and Schorske surmises that Athena was chosen because she’s the Godess of Wisdom and that’s as good as any for a Parliament.

Museum of Art History (Kunsthistorisches Museum)

Opened in 1891, it’s Renaissance style is typical of the learning institutions around the Ring Road: the University, the Museum of Natural History, and the Academy of Fine Arts.

Austrian Postal Savings Bank (Österreichische Postsparkasse)

Completed in 1906, this was one of the final buildings put on the Ringstraße. It is an excellent expression of Art Nouveau or Jungenstil acrchitecture, thoroughly modern and in stark contrast to everything above. Designed by Otto Wagner, he was a early proponent of function over decoration, although that idea had not yet reached its mid-20th century extremes. I personally love this building. I encourage you to just do an image search for it.

The role of the Ringstraße

The Vienna tourist website refers to the Ring Road as the “display window” of the former Danubian monarchy. This is certainly true and the monumental buildings above show that. But we should also keep in mind that cafes, apartment buildings and 1st floor shops lined the road as well. Outside of government, this was the “display window” for the Viennese as well.

Cafe culture we will get to later, as it is a large topic. But in an era before in-home entertainment (except for maybe a piano or some games), a turn about the Ring Road was a regular part of people’s lives. Freud took an almost daily walk (some would say it was almost a jog) around it’s six kilometer perimeter. His apartment building, cafe and the University where he worked were all on the Road. Hitler wandered the road during his unemployed Vienna days because it had “a magic effect upon me, as if it were a scene from The Thousand and One Nights.”

Flâneur may be a French word, but its meaning (idle strolling) may be certainly applied to the Viennese use of their new wide-open boulevard and the many parks and squares created by its construction in the middle of their medieval city. From this point forward, almost all the locations mentioned in Vienna will be either on or have a point of reference to the Ringstraße.

My essential source here is Carl E. Schorske’s 1979 book Fin-de-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture, specifically the essay “The Ringstrasse, Its Critics, and the Birth of Urban Modernism.” This book won the 1981 Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction and has been crucial to my preparation for this newsletter.