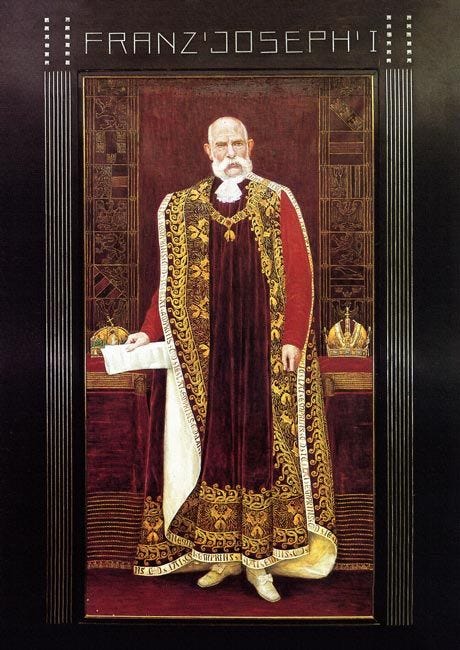

It’s impossible to talk about the Dual Monarchy and the fin-de-siècle without addressing Emperor Franz Joseph I. He ruled the Empire for the entire period I am addressing and his particular brand of politics colors almost everything we will discuss. He is the sixth-longest reigning monarch in the history of the world, sitting on the throne from 1848 until 1916.

Born in Austria’s version of Versailles, Schönbrunn Palace just outside of Vienna, in 1830, Franz Joseph was the son of the Archduke Franz Karl and was not slated for the throne. That burden went to his cousin, the genetically unfortunate Ferdinand I. When the Year of Revolutions (1848) arrived, Ferdinand was unable to rule and unable to comprehend what was going on around him. When told of Vienna, Prague, Northern Italy, and Budapest rising up against the monarchy, Ferdinand reportedly asked his ministers, “But are they allowed to do that?”

Ministers in Vienna then concocted what can be seen as a bloodless, intra-family coup. Ferdinand was easily persuaded to abdicate in the favor of his young cousin Franz Joseph. Technically, Franz Joseph’s father was next in line for the throne but he was generally uninterested in ruling especially during a crisis and so his son was brought to the fore.

Thus began Franz Joseph’s reign. Born of desperate necessity, the Austrian Army began ruthlessly crushing opposition with the help of Imperial Russian forces, especially in Hungary. The Empire was saved but at great cost of life and treasure and with a firmly conservative mindset embedded in the Emperor and his Ministers.

The rest of his reign can been seen as a series of desperate actions to keep the Empire together, coupled with a few bizarre and unfortunate pieces of bad luck. In 1853 a Hungarian nationalist almost succeeded in assassinating Franz Joseph, further inculcating a atmosphere of fear. (The Votivkirche is the physical remembrance of this event.)

In the 1850s Austria’s small participation in the Crimean War on the side of English, French and Ottomans severed its long-time friendship with Russia, isolating it diplomatically. The Italian Wars of Independence severed northern Italy from Austria and again burned tremendous amounts of treasure to no advantage. Then, in 1866, the Austro-Prussian War brought defeat at the Battle of Königgrätz at the hands of a much more technically advanced Prussian (soon to be German) Army. Franz Joseph, as a result, lost one of his titles: President of German Confederation. Austrian leadership of greater Germany was now dead and the stage was set for the declaration of Imperial Germany dominated by Prussia.

The stage was now set for compromise. The Army had been shown to be weak and ineffectual over and over again. The military dictatorship that had been ruling in Hungary since 1848 was now suspect and liberal aristocratic wanted change. They were willing to provide recognition to the state in exchange for more local freedom. This is why the Dual Monarchy is born in 1867, one year after the Austro-Prussian War. This is the beginning of Imperial and Royal (kaiserlich und königlich). In broad terms, it was attempt by Franz Joseph and Vienna to prevent yet another rebellion by Budapest in a moment of weakness.

Further revolution was avoided. And yet it was doomed to long-term failure. The pro-compromise Liberal Party within Hungary was supported by a very small group of aristocratic, landed Hungarians as well as ethnic Slovaks, Romanians and Croatians. This was enough for a very slight majority in the Hungarian Parliament. However, most non-elite Hungarians hated the Compromise and voted for more aggressive anti-compromise, pro-independence agendas. The spirit of 1848 did not go away and the Empire remained a police state throughout its existence.

Franz Joseph has personal as well as political burdens. His brother, Maximilian, jaunted off to Mexico to because Emperor briefly, supported by a weary French Army. But that did not last long and Maximilian was executed by firing squad.

Franz Joseph’s relationship with his wife, Empress Elisabeth, was increasingly strained, especially after the Mayerling Affair (see previous post) and she tended to be away from Vienna for long stretches of time. She was eventually assassinated by an Italian anarchist in 1898 while visiting Geneva.

Franz Joseph’s brother, Archduke Ludwig Viktor, was openly homosexual and reportedly held outrageous parties that scandalized the family until he was exiled from Vienna.

Finally, Franz Joseph clashed continuously with his new heir. After Rudolph committed suicide at Mayerling and Franz Ferdinand was made the heir, it was found that they could not work together. Franz Joseph shared very little his heir and a frustrated Franz Ferdinand early on gave up trying to ingratiate himself with his uncle. They were operating entirely separately.

Later, we’ll see how this conservative ruler reacted to the dynamic culture around him, when we start looking more closely at the art and music.

In closing, a man in the 20th century actually held these titles:

His Imperial and Apostolic Majesty,

Franz Joseph I,

By the Grace of God,

Emperor of Austria,

King of Hungary and Bohemia,

King of Lombardy and Venice, of Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, Lodomeria and Illyria; King of Jerusalem etc., Archduke of Austria; Grand Duke of Tuscany and Cracow, Duke of Lorraine, of Salzburg, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola and of the Bukovina; Grand Prince of Transylvania; Margrave of Moravia; Duke of Upper and Lower Silesia, of Modena, Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla, of Auschwitz [Oświęcim] and Zator, of Teschen [Cieszyn/Těšín], Friuli, Ragusa [Dubrovnik] and Zara [Zadar]; Princely Count of Habsburg and Tyrol, of Kyburg, Gorizia and Gradisca; Prince of Trent [Trento] and Brixen [Bressanone]; Margrave of Upper and Lower Lusatia and in Istria; Count of Hohenems, Feldkirch, Bregenz, Sonnenberg, etc.; Lord of Trieste, of Cattaro [Kotor], and in the Wendish Mark; Grand Voivode of the Voivodina of Serbia etc. etc.

Come back!